After a 6-month haitus, I am finally writing another post. Rummaging through my dad's office, I found one of my great-grandfather David Lester McBride's old priesthood manuals, A Seventy's Course in Theology. The Seventy's Course was a series of priesthood manuals authored by B. H. Roberts and originally used by, you guessed it, Seventies Quorums, between 1907 and 1911. The book in my dad's credenza consisted of volumes 1 and 2, bound together.

I have long been familiar with these manuals; even read lengthy passages. In fact, I'll admit I envy somewhat the brethren who used this course for their lessons. The subject matter is often intriguing, with lesson titles such as "The Inexorableness of Law" and "Patristic Notions of God." But it was not the content of the manuals that caught my attention yesterday.

David Lester wrote his name inside the back cover, along with the following address: "287 Bainbridge St. Brooklyn." We knew great-grandpa was serving a mission to New York at that time. Now we know where he lived for at least part of the time. Here is a Google Maps satellite view:

View Larger Map

There appears to be a building there that may have been his apartment building, though it is difficult to be sure. Here is a Google Street View shot:

View Larger Map

Need to do a little more research on this on. If I remember correctly, the newspaper report of his funeral included a short account of a talk given by one of his companions. I'll have to dig that out. Also, we have a photo of him with his companion taken during his mission. Need to post that, too.

Sunday, October 31, 2010

Sunday, April 18, 2010

More photographs of Mullenark

Here are some nice, medium resolution photos of Mullenark Castle I found the other day. The first one is of the front of the building. Nothing new, but kind of a nice shot.

The second is interesting because it shows one of the front towers at the vantage from which grandpa's fellow platoon members would have seen them. Fairly imposing, when you consider, as Frank Perozzi said, there were snipers firing at them from the turrets as they dug their fox holes.

The third photo is of the mill house just to the southeast of the house. The moat ran right along this structure and it was positioned near the mill pond, too.

The last photo is of one of the walls surrounding the estate. These were the walls grandpa spoke of using to skirt the property and make their way into Schophoven to the northwest. According to the photo's description (as "translated" by Google), the damage to the wall was sustained during World War II. It's conceivable that the scars were inflicted by the artillery preparation that preceded the infantry assault on Mullenark the night of December 13, 1944.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

David Lester McBride's Draft Card

David Lester McBride and Annie Leishman Brown McBride were married 18 January 1911, the outset of a turbulent decade. Neta was born late that same year, Reba joined the family early in 1913 and Annie Ruth was born in 1915.

Direct U.S. military involvement in World War I began on 6 April 1917 after three years of stubborn isolationism. Initially only 32,000 men volunteered. The commitment to send a large U.S. force to Europe led to the passage of the Selective Service Act. Under its mandate, three draft lotteries were held during the next 18 months. The first, which was held on 5 June 1917, required that eligible men born between 1886 and 1896 (ages 20-30) register for the draft. The second was one year later to the day, for those who had turned 20 during the previous 12 months. Of the combined 11 million men who registered for these two lotteries, almost 2 million were actually drafted. Unfortunately, this was not enough.

At the request of the War Department, Congress amended the Selective Service Act in August 1918 to expand the age range to include all men 18 to 45. Suddenly 36-year-old father of 4, David Lester McBride, was draft eligible. He was to report to the Cache County draft board on September 12 to register for the third draft lottery.

The previous January, David and Annie had welcomed their first son into the family, Ward Lester. Ward was only 7 months old at the time of the draft lottery. I can only imagine the anxiety David and Annie experienced when they heard about the draft. He reported that day and filled out his draft registration card. Here is the card:

Direct U.S. military involvement in World War I began on 6 April 1917 after three years of stubborn isolationism. Initially only 32,000 men volunteered. The commitment to send a large U.S. force to Europe led to the passage of the Selective Service Act. Under its mandate, three draft lotteries were held during the next 18 months. The first, which was held on 5 June 1917, required that eligible men born between 1886 and 1896 (ages 20-30) register for the draft. The second was one year later to the day, for those who had turned 20 during the previous 12 months. Of the combined 11 million men who registered for these two lotteries, almost 2 million were actually drafted. Unfortunately, this was not enough.

At the request of the War Department, Congress amended the Selective Service Act in August 1918 to expand the age range to include all men 18 to 45. Suddenly 36-year-old father of 4, David Lester McBride, was draft eligible. He was to report to the Cache County draft board on September 12 to register for the third draft lottery.

The previous January, David and Annie had welcomed their first son into the family, Ward Lester. Ward was only 7 months old at the time of the draft lottery. I can only imagine the anxiety David and Annie experienced when they heard about the draft. He reported that day and filled out his draft registration card. Here is the card:

While in good health and otherwise eligible, David was not selected. Thankfully, he was allowed to remain home to care and provide for his growing family. They experienced war on the home front. One inventory of typical wartime activities experienced by many Utahns included planting "victory gardens," preserving food, volunteering for work in the beet fields and on Utah's fruit farms, purchasing Liberty Bonds, giving "Four Minute" patriotic speeches, collecting money for the Red Cross, using meat and sugar substitutes, observing meatless days, knitting socks, afghans, and shoulder wraps, weaving rugs for soldiers' hospitals, making posters, prohibiting the teaching of the German language in some schools, and cultivating patriotism at every opportunity.

During these same trying years (1917-1920), an influenza pandemic swept the nation killing an estimated 600,000 Americans. In 1920, the deadly virus claimed the lives of 5-year-old Annie Ruth and 2-year-old Ward Lester. Neta recalled: "When the little kids died, I [was] 7. I can remember when they carried those little things out, and how everyone was so sick.... Mother, seems like that all she did was cry.... She couldn’t get over those kids dying... They’d done something out there on that porch and she wouldn’t ever let us paint over it because she says that was the last finger prints... she’d ever see."

Annie, already prone to anxiety and depression, would never fully recover from this terrible blow. She died in the Utah State Hospital in Provo on 27 October 1932. But that is a subject for another day.

Annie, already prone to anxiety and depression, would never fully recover from this terrible blow. She died in the Utah State Hospital in Provo on 27 October 1932. But that is a subject for another day.

Monday, March 22, 2010

Group Photo at Place de la Concorde in Paris

Once the Timberwolves reached Cologne, their advance halted for a few weeks. At the time, Cologne was Germany's third largest city. It stood on the west bank of the Rhine River, the last natural barrier between the Allies and what they anticipated would be a dagger to the heart of Germany: an attack on the industrial Ruhr region. Lee's battalion captured the small town of Efferen on the approaches to Cologne early in February 1945, then moved into a residential area in the southern part of Cologne on 8 February. While most of the division underwent a rigorous training routine and practiced river crossings in nearby lakes, Grandpa Lee took a trip to Paris. His account of this time reads:

"At this time there became available a number of 3-day passes to Paris. It seemed an opportunity worth accepting and so together with some 50 or so others it was back away from the front to France. It was cold and gray the whole time we were in Paris but it was also interesting to see the many sights—the Eiffel Tower, Arc de Triumph, Cathedral of Notre Dame, Louvre etc. We had a group photo taken at the Place de la Concorde near the Arc de Triumph at the head of the Champs de Elysees."

Here is the photo (courtesy of Marilyn Hansen). Grandpa is the 7th from the right on the front row:

Here is a photo my kids and I took recently at the same fountain. Not much has changed since 1945:

Lee continued: "While 'enjoying' the sights of Paris we received word that a bridge across the Rhine had been captured intact. All passes were cancelled and it was back to Cologne on the first train." This of course was the bridge at Remagen. Upon his return, he joined his battalion in an assembly area near Bad Honnef (a few miles north of Remagen) and on Feb. 23 they crossed the Rhine on pontoon bridges. They were riding the trucks and tanks of the 3rd Armored Division. A fellow member of the 414th described the crossing: "The pontoon bridge over the Rhine was a carnival ride. The pontoon you were on was down in the water, the one in front of you was about 3 or 4 feet above you, and the one behind popped up as soon as you drove off of it."

"At this time there became available a number of 3-day passes to Paris. It seemed an opportunity worth accepting and so together with some 50 or so others it was back away from the front to France. It was cold and gray the whole time we were in Paris but it was also interesting to see the many sights—the Eiffel Tower, Arc de Triumph, Cathedral of Notre Dame, Louvre etc. We had a group photo taken at the Place de la Concorde near the Arc de Triumph at the head of the Champs de Elysees."

Here is the photo (courtesy of Marilyn Hansen). Grandpa is the 7th from the right on the front row:

Here is a photo my kids and I took recently at the same fountain. Not much has changed since 1945:

Lee continued: "While 'enjoying' the sights of Paris we received word that a bridge across the Rhine had been captured intact. All passes were cancelled and it was back to Cologne on the first train." This of course was the bridge at Remagen. Upon his return, he joined his battalion in an assembly area near Bad Honnef (a few miles north of Remagen) and on Feb. 23 they crossed the Rhine on pontoon bridges. They were riding the trucks and tanks of the 3rd Armored Division. A fellow member of the 414th described the crossing: "The pontoon bridge over the Rhine was a carnival ride. The pontoon you were on was down in the water, the one in front of you was about 3 or 4 feet above you, and the one behind popped up as soon as you drove off of it."

Friday, March 19, 2010

Battle for Raguhn

The battle of Raguhn was where Lee earned his Silver Star. It is one of the few experiences of which he gives a detailed account. In addition to his account, we have his citation, and a retelling of the battle from the perspective of another Timberwolf, William Bracey, who also participated in the battle. I've done my best to reconstruct the events using these and a few other sources.

Raguhn sits astride the Mulde River, which splits in two channels at Raguhn, creating a substantial island in the center of the town. The portion of the town to the west of the river channels had been taken the previous day by a coordinated air-armor-infantry attack in which another company of 2nd Battalion 414th Regiment had participated. F Company "entered the city late in the afternoon and found a small tank repair crew with two partially disabled tanks already there." The Battalion CO, Maj. John Melhop ordered F Company to remain in Raguhn the evening of the 16th while some of the other units continued their mopping up of the area.

According to fellow platoon member Tom Lacek, the strength of F Company was about thirty men, down from a full complement of 180. Lee’s platoon had fared better than some—there were still about nine platoon members—but they were feeling decimated. At the time, 2nd Battalion was still attached to the 3rd Armored Division, and had been riding tanks from town to town in coordinated combat. They found a house near the railroad tracks, that run north-south parallel to the river on the western of side Raguhn and settled in for what they hoped would be a peaceful night.

They were in for a rude awakening. They were notified by the Battalion that intelligence indicated a German counterattack in the making. Raguhn and nearby towns Thurland (six miles to the west) and Siebenhausen, (about five miles south) were the focus of the counterattack late that night. The 2nd Battalion CP in Thurland was completely overrun, and the troops quartered in Raguhn were almost completely surrounded.

William Bracey of H Company (the only other company in town) was among the first who was aware that the attack had reached them. He heard shouting in German outside his door at No. 4 Markesche Strasse, on the western outskirts of town at about 3:00 the morning of the 17th. He reported that about “about 50 German infantrymen came by the doorway, in single file, close enough that I could have reached out and touched them.” He and his comrades were not detected because they had parked their Jeeps and half-track on the north and south sides of No. 4 behind high fences.

The map below shows the location of No. 4 in Raguhn, just east of the railway. Further to the east, you'll see the several branches of the Mulde:

Word of the counterattack quickly reached the F Company men. As Lee put it: “Much to our chagrin we awakened in the morning to find ourselves, one infantry platoon plus the tank mechanics, surrounded by the enemy—cut off from our support.”

Lee’s “platoon leader at the time was unable to function due to battle fatigue.” As Assistant Platoon leader, Tech Sgt. McBride assumed command of the platoon. “We made [the Platoon leader] comfortable in a basement and went out to see what needed doing.” As a later citation recorded: “[Lee] voluntarily left his covered position and assumed command of a platoon which was attempting to dislodge the enemy from his newly won positions. After a fierce fight, during which he constantly exposed himself to withering enemy fire, Sergeant McBride’s men were surrounded by the superior enemy force.” Lee put it more modestly: “It was routine work clearing the enemy from all of the buildings in town with the exception of a large factory.”

It is apparent that this house-to-house fighting, though routine, was no walk in the park. Tom Lacek recalled that they were “up all night,” repelling the German counterattack. Bracey observing the action from the windows of his house added, “Our F Company riflemen soon engaged the Germans, forcing them into a factory, and house across the street from the factory.”

The factory was “a brick building of one story located at the extreme edge of town adjacent to open fields. The enemy command post was located in this building and the German troops were ‘dug in’ in the fields surrounding the town.” It was apparently very close to the house on Markesche Strasse.

Since an infantry attack on the factory would have a been a dangerous and costly endeavor, the F Company doughs decided to “bring one of the tanks down to the building as a persuasive force.” The tanks were several blocks from the factory, just east of the railroad tracks. McBride contacted the tank mechanics, who “were very reluctant to get involved but finally agreed to bring the better of the two tanks along and see if it could be of help.” He then “courageously ran a gauntlet of enemy fire to lead [the] tank forward.” According to his account, the then “positioned the tank close to a window of the building and placed the muzzle of the cannon directly facing the window. Fortunately there was nothing wrong with that part of the tank and we sent a round into the building. The shrapnel ricocheting about the inside of that building must have been somewhat disconcerting to the German officers inside. Another invitation to surrender was tendered. This time they offered to leave the town and take all their people from the fields about the town with them.”

Bracey, after attempting unsuccessfully to help clear the Germans from the house across from the factory, returned to No. 4 and watched the situation unfold: “Our tank moved into position to fire on the factory and house. At this point, a white flag appeared, and through an interpreter, the Germans asked for safe passage through our line to their positions on the island and east bank of the Mulde River.” According to Bracey's account, Lee, who was directing the fire of the tanks, replied: “What the hell do they think we are playing—checkers? Tell them to surrender or we’ll blow up the factory and them with it!”

Lee’s continues humorously: “We refused their generous offer and presented them with another round or two of fire from the big gun on the tank. After the reverberations died down we again invited them and all their men from the surrounding fields to join us with hands behind their heads. This time they agreed that might be a good idea after all and proceeded to line up the entire unit in the courtyard” across the street from the factory to the north.

They “sent to the basement room where we had left our platoon leader and had him come to accept the surrender of over a hundred German troops.” Lee noted: “You see, I was leading the platoon [but] as a non-commissioned officer was not worthy to accept the surrender of the German officers and their men.” Lee was awarded a Silver Star for this action, which he insisted, “should have gone to the platoon, not the Platoon Sergeant.” Here is the citation in full:

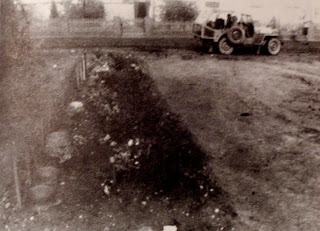

After the counterattack was squelched Major Melhop returned in a jeep to Raguhn where he found things under control thanks to the quick thinking and dash of those few remaining F Company members. Melhop took pictures of the large number of German bodies that had been placed in open graves victims of the house-to-house fight. The following is one of those pictures:

Raguhn sits astride the Mulde River, which splits in two channels at Raguhn, creating a substantial island in the center of the town. The portion of the town to the west of the river channels had been taken the previous day by a coordinated air-armor-infantry attack in which another company of 2nd Battalion 414th Regiment had participated. F Company "entered the city late in the afternoon and found a small tank repair crew with two partially disabled tanks already there." The Battalion CO, Maj. John Melhop ordered F Company to remain in Raguhn the evening of the 16th while some of the other units continued their mopping up of the area.

According to fellow platoon member Tom Lacek, the strength of F Company was about thirty men, down from a full complement of 180. Lee’s platoon had fared better than some—there were still about nine platoon members—but they were feeling decimated. At the time, 2nd Battalion was still attached to the 3rd Armored Division, and had been riding tanks from town to town in coordinated combat. They found a house near the railroad tracks, that run north-south parallel to the river on the western of side Raguhn and settled in for what they hoped would be a peaceful night.

They were in for a rude awakening. They were notified by the Battalion that intelligence indicated a German counterattack in the making. Raguhn and nearby towns Thurland (six miles to the west) and Siebenhausen, (about five miles south) were the focus of the counterattack late that night. The 2nd Battalion CP in Thurland was completely overrun, and the troops quartered in Raguhn were almost completely surrounded.

William Bracey of H Company (the only other company in town) was among the first who was aware that the attack had reached them. He heard shouting in German outside his door at No. 4 Markesche Strasse, on the western outskirts of town at about 3:00 the morning of the 17th. He reported that about “about 50 German infantrymen came by the doorway, in single file, close enough that I could have reached out and touched them.” He and his comrades were not detected because they had parked their Jeeps and half-track on the north and south sides of No. 4 behind high fences.

The map below shows the location of No. 4 in Raguhn, just east of the railway. Further to the east, you'll see the several branches of the Mulde:

Lee’s “platoon leader at the time was unable to function due to battle fatigue.” As Assistant Platoon leader, Tech Sgt. McBride assumed command of the platoon. “We made [the Platoon leader] comfortable in a basement and went out to see what needed doing.” As a later citation recorded: “[Lee] voluntarily left his covered position and assumed command of a platoon which was attempting to dislodge the enemy from his newly won positions. After a fierce fight, during which he constantly exposed himself to withering enemy fire, Sergeant McBride’s men were surrounded by the superior enemy force.” Lee put it more modestly: “It was routine work clearing the enemy from all of the buildings in town with the exception of a large factory.”

It is apparent that this house-to-house fighting, though routine, was no walk in the park. Tom Lacek recalled that they were “up all night,” repelling the German counterattack. Bracey observing the action from the windows of his house added, “Our F Company riflemen soon engaged the Germans, forcing them into a factory, and house across the street from the factory.”

The factory was “a brick building of one story located at the extreme edge of town adjacent to open fields. The enemy command post was located in this building and the German troops were ‘dug in’ in the fields surrounding the town.” It was apparently very close to the house on Markesche Strasse.

Since an infantry attack on the factory would have a been a dangerous and costly endeavor, the F Company doughs decided to “bring one of the tanks down to the building as a persuasive force.” The tanks were several blocks from the factory, just east of the railroad tracks. McBride contacted the tank mechanics, who “were very reluctant to get involved but finally agreed to bring the better of the two tanks along and see if it could be of help.” He then “courageously ran a gauntlet of enemy fire to lead [the] tank forward.” According to his account, the then “positioned the tank close to a window of the building and placed the muzzle of the cannon directly facing the window. Fortunately there was nothing wrong with that part of the tank and we sent a round into the building. The shrapnel ricocheting about the inside of that building must have been somewhat disconcerting to the German officers inside. Another invitation to surrender was tendered. This time they offered to leave the town and take all their people from the fields about the town with them.”

Bracey, after attempting unsuccessfully to help clear the Germans from the house across from the factory, returned to No. 4 and watched the situation unfold: “Our tank moved into position to fire on the factory and house. At this point, a white flag appeared, and through an interpreter, the Germans asked for safe passage through our line to their positions on the island and east bank of the Mulde River.” According to Bracey's account, Lee, who was directing the fire of the tanks, replied: “What the hell do they think we are playing—checkers? Tell them to surrender or we’ll blow up the factory and them with it!”

Lee’s continues humorously: “We refused their generous offer and presented them with another round or two of fire from the big gun on the tank. After the reverberations died down we again invited them and all their men from the surrounding fields to join us with hands behind their heads. This time they agreed that might be a good idea after all and proceeded to line up the entire unit in the courtyard” across the street from the factory to the north.

They “sent to the basement room where we had left our platoon leader and had him come to accept the surrender of over a hundred German troops.” Lee noted: “You see, I was leading the platoon [but] as a non-commissioned officer was not worthy to accept the surrender of the German officers and their men.” Lee was awarded a Silver Star for this action, which he insisted, “should have gone to the platoon, not the Platoon Sergeant.” Here is the citation in full:

After the counterattack was squelched Major Melhop returned in a jeep to Raguhn where he found things under control thanks to the quick thinking and dash of those few remaining F Company members. Melhop took pictures of the large number of German bodies that had been placed in open graves victims of the house-to-house fight. The following is one of those pictures:

Sunday, March 14, 2010

Sons of the Servants of St. Bridget

The McBride's were an early Scottish clan. Many of these clans looked to a patron saint as a source of unity. Our clan adopted St. Bridget as their patron. Who was St. Bridget? Bridget was a famous Abbess of Kildare, Ireland. She died in 525 A.D. This is the entry on St. Bridget in the Catholic Encyclopedia:

Dictionaries of patronymic names suggest that the following additional names are all variations on this theme: Mac Bride, St. Bridget, McBrides, Mac Brides, Mc Bryde, Bride, Brides, Bridget, Bridgets, Bryget, Bryde and Brydes, Mac Kilbride, Killbride, Bridie, Brydie, Bridey, and McBryd. The McBride name in its current formulation (if not exact spelling--"McBryd") originated in 1329 in Scotland.

St. Bridget arrived in Ireland a few years after St. Patrick. Her father was an Irish lord named Duptace. As Bridget grew up, she became holier and more pious each day. She loved the poor and would often bring food and clothing to them. One day she gave away a whole pail of milk, and then began to worry about what her mother would say. She prayed to the Lord to make up for what she had given away. When she got home, her pail was full! Bridget was a very pretty young girl, and her father thought that it was time for her to marry. She, however, had given herself entirely to God when she was very small, and she would not think of marrying anyone. When she learned that her beauty was the reason for the attentions of so many young men, she prayed fervently to God to take it from her. She wanted to belong to Him alone. God granted her prayer. Seeing that his daughter was no longer pretty, her father gladly agreed when Bridget asked to become a Nun. She became the first Religious in Ireland and founded a convent so that other young girls might become Nuns. When she consecrated herself to God, a miracle happened. She became very beautiful again! Bridget made people think of the Blessed Mother because she was so pure and sweet, so lovely and gentle. They called her the "Mary of the Irish."A story, I'm sure, that loses nothing in the telling. The clan was so zealous in their devotion to St. Bridget that it came to define them. They were known as the Gillebride, in other words "Servants of Bridget" or "Followers of Saint Bridget," "gille" being a Gaelic word for "servant," and "bride" a contracted form of "Bridget." Clan surnames like this (with the word "servant" or "devotee" followed by the name of a saint) were fairly common. Their descendants were often known as Macgillbride (or the Irish equivalent "Mac Giolla Bhride"), or "Sons of the Followers of Bridget," and eventually McBride. I imagine the the celibate Bridget might have rankled at the idea of this group calling themselves "Sons of Bridget." Libelous!

Dictionaries of patronymic names suggest that the following additional names are all variations on this theme: Mac Bride, St. Bridget, McBrides, Mac Brides, Mc Bryde, Bride, Brides, Bridget, Bridgets, Bryget, Bryde and Brydes, Mac Kilbride, Killbride, Bridie, Brydie, Bridey, and McBryd. The McBride name in its current formulation (if not exact spelling--"McBryd") originated in 1329 in Scotland.

Friday, March 12, 2010

More on Müllenark

The word “Müllenark” in middle-high-German meant “mill dam.” The Müllenark estate was the location of a large mill, and the barons who lived there were known by the name Müllenark as early as the 12th century. The mill was operated by water diverted from the Roer River and retained in a mill pond just to the southeast of the house. The pond and moat mentioned in the various accounts of the battle were respectively the mill pond and the canal that diverted the river water to the mill works. Over the centuries, the Müllenark gristmill was used to grind grain, extract oils, and later to power saws, grinders and other machinery. At its peak, it boasted three large water wheels and serviced several towns in the area, including Schophoven. The mill works were located, in part, in the southern wing of the house, while the northern and western portions of the structure were residential. Most of the machinery operated by the mill in the early 20th century was located in the house located at the southwest corner of the great house. It is possible that the large cellar behind the house was originally used as cold storage for mill products such as flour and oil.

Just for fun, here is Lee's Bronze Star Citation earned at Müllenark on Dec. 13, 1944:

414th Regiment WWII Bibliography

I thought I might post a short list of recommended reading related to Lee McBride's unit and the campaigns in which he was involved. Published sources only:

1. Leo Arthur Hoegh, Timberwolf Tracks: The History of the 104th Infantry Division, 1942-1945 . A great starting point. Gives a thorough, if sometimes jumbled account of the division's WWII history. Don't miss Sgt. Frank Perozzi's account of the Mullenark attack. Very vivid.

. A great starting point. Gives a thorough, if sometimes jumbled account of the division's WWII history. Don't miss Sgt. Frank Perozzi's account of the Mullenark attack. Very vivid.

2. Derek Zumbro, Battle for the Ruhr: The German Army's Final Defeat in the West (Modern War Studies) . This book takes the German perspective on the Ruhr encirclement. It is fascinating to read about what was happening on the other side of the receding German front, opposite the 3rd Armored spearhead. (Remember, Lee rode the tanks of the 3rd Armored during the Ruhr campaign, from late Feb. to April.)

. This book takes the German perspective on the Ruhr encirclement. It is fascinating to read about what was happening on the other side of the receding German front, opposite the 3rd Armored spearhead. (Remember, Lee rode the tanks of the 3rd Armored during the Ruhr campaign, from late Feb. to April.)

3. Harry Yeide, The Longest Battle: September 1944-February 1945: From Aachen to the Roer and Across . The Roer ended up figuring in the battle plans of First Army a lot longer than anticipated. A very important look at a battle that is almost always neglected by popular histories of the war in Europe. A thorough account of the battle in the Eschweiler-Weisweiler corridor and the northern Hurtgen, the impact of the demolition of the Roer dams, and more. (In other words, the first month of Lee McBride's combat experience.)

. The Roer ended up figuring in the battle plans of First Army a lot longer than anticipated. A very important look at a battle that is almost always neglected by popular histories of the war in Europe. A thorough account of the battle in the Eschweiler-Weisweiler corridor and the northern Hurtgen, the impact of the demolition of the Roer dams, and more. (In other words, the first month of Lee McBride's combat experience.)

4. Normandy to Victory: The War Diary of General Courtney H. Hodges and the First U.S. Army (American Warriors Series) . Some interesting perspective on how First Army Commander General Courtney Hodges viewed the performance and accomplishments of the Timberwolves.

. Some interesting perspective on how First Army Commander General Courtney Hodges viewed the performance and accomplishments of the Timberwolves.

5. Gerald Astor, Terrible Terry Allen: The Soldiers' General . Allen was a soldier's general. He was incredibly popular with the men he commanded. They always knew Allen was looking out for them. This biography covers the Timberwolves' campaign in detail.

. Allen was a soldier's general. He was incredibly popular with the men he commanded. They always knew Allen was looking out for them. This biography covers the Timberwolves' campaign in detail.

6. Andre Sellier, A History of the Dora Camp: The Untold Story of the Nazi Slave Labor Camp That Secretly Manufactured V-2 Rockets . Written by a French survivor of the Dora Camp near Nordhausen who went on to obtain historical training. Absolutely amazing account; provides not only a lot of first hand information and interviews but the single best statistical analysis of the grim mathematics of this Nazi death camp.

. Written by a French survivor of the Dora Camp near Nordhausen who went on to obtain historical training. Absolutely amazing account; provides not only a lot of first hand information and interviews but the single best statistical analysis of the grim mathematics of this Nazi death camp.

7. John A. Melhop, The Memoirs of a Maverick Major. This book was a self-published account of John Melhop's experiences that is now out of print. Melhop was a member of the 2nd Battlalion Staff and its acting commander for a period of time. The book contains detailed accounts and several photos.

8. Charles B. McDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign. The official history of the battle. It has been posted online in its entirety.

2. Derek Zumbro, Battle for the Ruhr: The German Army's Final Defeat in the West (Modern War Studies)

3. Harry Yeide, The Longest Battle: September 1944-February 1945: From Aachen to the Roer and Across

4. Normandy to Victory: The War Diary of General Courtney H. Hodges and the First U.S. Army (American Warriors Series)

5. Gerald Astor, Terrible Terry Allen: The Soldiers' General

6. Andre Sellier, A History of the Dora Camp: The Untold Story of the Nazi Slave Labor Camp That Secretly Manufactured V-2 Rockets

7. John A. Melhop, The Memoirs of a Maverick Major. This book was a self-published account of John Melhop's experiences that is now out of print. Melhop was a member of the 2nd Battlalion Staff and its acting commander for a period of time. The book contains detailed accounts and several photos.

8. Charles B. McDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign. The official history of the battle. It has been posted online in its entirety.

Thursday, March 11, 2010

Samuel McBride and the Albany Committee of Safety and Correspondence

Committees of Safety and Correspondence

By the time the first shots of the war for independence were fired at Lexington in 1775, colonial Americans already had a firmly-rooted tradition of self-organizing on a local level. When there were questions their governments were not addressing or civil functions that they felt were not being adequately performed, they banded together as communities to seek solutions. These grass roots efforts took the form of committees, often called committees of inquiry, committees of safety, or committees of correspondence.

These committees had played a role in the French-Indian War in 1760 as well as in community life of many colonial settlements. They were essentially democratic in nature, their members usually being elected by local inhabitants, often without regard to land ownership. In this respect they represented early and foundational experiments in self-government.

In the wake of the Stamp Act in 1765, there was an unprecedented flurry of this type of grass-roots activism. The growing mistrust of the Crown, parliament, and significantly, the crown-appointed municipal and colonial governments among a large segment of the population, led to the formation of dozens of these committees from New England to the southern colonies. Most of these committees were formed in large commercial centers or port cities. These groups differed from previous committees in two important ways.

First, they were organized on a much broader scale than ever before. This was due in part to the fact that they were formed to address needs that were broader than simple local concerns. Therefore, there were not only many more committees, but there was also measure of unity of cause that had not previously existed between committees. This cohesiveness contributed to the formation of the provincial congresses and the Continental Congress and underscored the need for the committees to correspond on matters of mutual interest.

The second key characteristic that differentiated these committees was that they tended to be much more radical in nature than past committees. Many of their activities could rightly be considered treasonous from a British perspective.

The desire to declare independence from the British government was something that took root at different times for different people. There were many, including notable Bostonians Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who felt this need from the beginning. The ideals of independence developed more slowly in others, propelled along by events such as the outbreak of violence in Massachusetts.

Others remained utterly unconvinced. For Tories or loyalists, the idea of independence seemed ludicrous, even worth fighting against. The dangers introduced to the war effort by these loyalists were enormous. There was a pressing need for immediate local oversight of loyalist activity in order to vouchsafe the successful prosecution of the war and protect the cause of liberty.

The activities of these Committees of Safety and Correspondence just prior to and during the war varied greatly, but there was an overriding focus on providing a civil authority to supply direction for the local militias, on weeding out subversive elements (read “loyalists”) from the communities they served, and on disseminating the ideals of the revolution as broadly as possible. To put it simply, they were in the business of carrying out the war on a local level.

As the war progressed, these committees became the hands of the Continental Congress, taking their general direction from congress, while operating autonomously in their local spheres. In this way congress and committee acted as a bridge between the British government and the state and federal governments that would eventually supplant them.

The Albany Committee

The Albany Committee of Safety and Correspondence held its first meeting on 24 January of 1775. It began at the city level, but quickly spread to incorporate the entire county. In addition to the representatives from the three wards of Albany City, subcommittees were formed in each town or district. There were as many as 19 of these subcommittees formed, including groups in Saratoga and Schenectady. On 17 February 1776, these various local committees formed “A General Association agreed to and subscribed by the Members of the several Committees of the City and County of Albany.”

The minutes of the Albany Committee meetings survived in large part, unlike the minutes of many other such committees. They were transcribed and published in 1923 under the direction of the New York State Historian, James Sullivan.

Sullivan’s introduction to the published edition of the minutes notes that “no committee of revolutionaries showed a more careful regard for the fact that they owed their powers to the people who elected them and no suggestion is even found that the members should continue in power beyond the time for which they were chosen.” He also provides this fantastic summary of the committee's wide range of responsibilities:

Samuel McBride’s Election to the Committee

The minutes for the meeting on 26 November 1776 contain the following report:

If he wasn’t an ardent patriot from the beginning, he may have been persuaded by news of the outbreak of hostilities in Massachusetts in early 1775. I found this interesting passage from a 1919 book entitled The Story of Old Saratoga by John Henry Brandow:

Was Samuel among those who participated in the transportation of the cannons? If not, he and his family would at least have been witnesses to the commotion. We know they were living at their Stillwater homestead as early as 1769. I imagine it would have been at once exciting and terrifying for 9-year-old Daniel to watch these events unfold. Whatever the case may be, Samuel's revolutionary credentials must have been fairly well established by the time of his election to the committee in November 1776.

By the time the first shots of the war for independence were fired at Lexington in 1775, colonial Americans already had a firmly-rooted tradition of self-organizing on a local level. When there were questions their governments were not addressing or civil functions that they felt were not being adequately performed, they banded together as communities to seek solutions. These grass roots efforts took the form of committees, often called committees of inquiry, committees of safety, or committees of correspondence.

These committees had played a role in the French-Indian War in 1760 as well as in community life of many colonial settlements. They were essentially democratic in nature, their members usually being elected by local inhabitants, often without regard to land ownership. In this respect they represented early and foundational experiments in self-government.

In the wake of the Stamp Act in 1765, there was an unprecedented flurry of this type of grass-roots activism. The growing mistrust of the Crown, parliament, and significantly, the crown-appointed municipal and colonial governments among a large segment of the population, led to the formation of dozens of these committees from New England to the southern colonies. Most of these committees were formed in large commercial centers or port cities. These groups differed from previous committees in two important ways.

First, they were organized on a much broader scale than ever before. This was due in part to the fact that they were formed to address needs that were broader than simple local concerns. Therefore, there were not only many more committees, but there was also measure of unity of cause that had not previously existed between committees. This cohesiveness contributed to the formation of the provincial congresses and the Continental Congress and underscored the need for the committees to correspond on matters of mutual interest.

The second key characteristic that differentiated these committees was that they tended to be much more radical in nature than past committees. Many of their activities could rightly be considered treasonous from a British perspective.

The desire to declare independence from the British government was something that took root at different times for different people. There were many, including notable Bostonians Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who felt this need from the beginning. The ideals of independence developed more slowly in others, propelled along by events such as the outbreak of violence in Massachusetts.

Others remained utterly unconvinced. For Tories or loyalists, the idea of independence seemed ludicrous, even worth fighting against. The dangers introduced to the war effort by these loyalists were enormous. There was a pressing need for immediate local oversight of loyalist activity in order to vouchsafe the successful prosecution of the war and protect the cause of liberty.

The activities of these Committees of Safety and Correspondence just prior to and during the war varied greatly, but there was an overriding focus on providing a civil authority to supply direction for the local militias, on weeding out subversive elements (read “loyalists”) from the communities they served, and on disseminating the ideals of the revolution as broadly as possible. To put it simply, they were in the business of carrying out the war on a local level.

As the war progressed, these committees became the hands of the Continental Congress, taking their general direction from congress, while operating autonomously in their local spheres. In this way congress and committee acted as a bridge between the British government and the state and federal governments that would eventually supplant them.

The Albany Committee

The Albany Committee of Safety and Correspondence held its first meeting on 24 January of 1775. It began at the city level, but quickly spread to incorporate the entire county. In addition to the representatives from the three wards of Albany City, subcommittees were formed in each town or district. There were as many as 19 of these subcommittees formed, including groups in Saratoga and Schenectady. On 17 February 1776, these various local committees formed “A General Association agreed to and subscribed by the Members of the several Committees of the City and County of Albany.”

The minutes of the Albany Committee meetings survived in large part, unlike the minutes of many other such committees. They were transcribed and published in 1923 under the direction of the New York State Historian, James Sullivan.

Sullivan’s introduction to the published edition of the minutes notes that “no committee of revolutionaries showed a more careful regard for the fact that they owed their powers to the people who elected them and no suggestion is even found that the members should continue in power beyond the time for which they were chosen.” He also provides this fantastic summary of the committee's wide range of responsibilities:

Everything pertaining to the successful prosecution of the war they felt to be within their province. It is an almost bewildering array of activities. (1) The raising, drafting, equipping, disciplining, training, officering, stationing and paying of troops. (2) The exemptions from military duty of those in essential industries or employment. (3) The detection, imprisonment, punishment and exile of the disaffected, spies and emissaries. (4) The suppression of organized revolts within the county and the prosecution of those guilty of speaking adversely of the patriot cause. (5) The support of those made poor by the war, the burial of their dead, and the helping of refugees. (6) The collection of the excise and the regulation of taverns. (7) The supervision of the construction of hospitals, barracks, forts and prisons. (8) The assumption of authority over the ordinances and powers of the city officers and the control of firemasters and fire regulations. (9) The regulation of prices for all kinds of articles, particularly of tea, sugar and salt. (10) The regulation and encouragement of trade and manufactures, and the inspection for bad products. (11) The handling of appeals to control housing difficulties, fix wages and prevent hoarding. (12) The encouragement of auxiliary aid such as the knitting of socks for the soldiers, collecting linen rags, medicines, and instruments. (13) The control of the issuance of paper money and of counterfeiting. 14) The quarantining against smallpox. 15) The rationing of food, particularly of wheat, and preventing its distillation into whiskey. (16) Subscriptions for the poor at home and in Boston. (17) The supervision of elections of members in subdistricts and for members of the Provincial Congress and the Legislature. (18) The maintenance of law and order. (19) The establishment of night watches. (20) The management of Indian affairs and relations.The minutes themselves begin with an oath of secrecy:

A large part of the time of the committee was taken up, as might be expected, with the tories, prisoners, deserters, murders, passes, rangers, protection of the loyal, robberies, plunder sequestration of tory property and treason, all very similar in character to the work carried on by the commissioners for detecting conspiracies. The patience exhibited in this work is at times surprising and if cruel treatment in the prisons is sometimes alleged, it must be attributed to lack of facilities rather than to intent.

Wee the Subscribers do swear on the Holy Evangelists of Almighty God that we will not devulge or make known to any Person or Persons whomsoever (except to a Member or Members of this Board) the Name of any Member of this Committee giving his Vote upon any Controverted matter which may be debated or determined in Committee, or the arguments used by such Person or Persons upon such Controverted Subject, and all other such matters as shall be given hereafter in Charge by the Chairman of this Committee to the Members to be kept secret under the sanction of this Oath, untill discharged therefrom by this Committee or a Majority of the subscribers or the Survivors of them, or unless when called upon as a Witness in a Court of Justice.The oath is followed by this statement of the purpose of the association:

Persu[a]ded that the salvation of the Rights and Liberties of America depends under God on the firm Union of it's Inhabitants, in a Vigorous prosecution of the Measures necessary for it's Safety; and convinced of the necessity of preventing the Anarchy and Confusion, which attend a Dissolution of the Powers of GovernmentThe committee met often, sometimes several times in a day to transact its business. These meetings took place in local taverns and eventually in the Albany City Hall. On 26 November 1776 they resolved that “the Committee of this County meet every Fort Night in the City Hall of the City of Albany or at such other place as shall be appointed, and that the said Meetings be on Tuesday, and that at least one Member from each respective District attend.”

We the Freemen, Freeholders and Inhabitants of the City and County of Albany being greatly Alarmed at the avowed Design of the Ministry, to raise a Revenue in American; and shocked by the bloody Scene now acting in the Massachusetts Bay Do in the most Solemn Manner resolve never to become Slaves; and do associate under all the Ties of Religion. Honour, and Love to our Country, to adopt and endeavour to carry into Execution whatever Measures may be recommended by the Continental Congress, or resolved upon by our Provincial Convention for the purpose of preserving our Constitution, and opposing the Execution of the several Arbitrary and oppressive Acts of the British Parliament untill a Reconciliation between Great Britain and America on Constitutional Principles (which we most ardently desire) can be obtained; And that we will in all things follow the Advice of our General Committee respecting the purposes aforesaid, the preservation of Peace and good Order and the safety of Individuals and private Property.

Samuel McBride’s Election to the Committee

The minutes for the meeting on 26 November 1776 contain the following report:

From a return of the Poll for the Election of Committee in the District of Saratoga it appears that the following Persons are duly Elected Viz.This is the earliest hard evidence we have that Samuel McBride had become converted to the cause of American independence. Of course later in the war he would go on to serve as a member of the Saratoga Regiment. What circumstances led him to feel the way he did? At what point did he become convinced?

George Palmer

Samuel Mackbride

William Patrick

Jacobus Swart

Matthew Winne

Calvan Skinner

Charles Moore

If he wasn’t an ardent patriot from the beginning, he may have been persuaded by news of the outbreak of hostilities in Massachusetts in early 1775. I found this interesting passage from a 1919 book entitled The Story of Old Saratoga by John Henry Brandow:

After the conquest of Canada by Britain in 1760, people very naturally believed that Old Saratoga had seen the last of war and bloodshed, hence, as we have learned, they began to flock to this fertile vale. But hardly had they settled here in appreciable numbers before Mother England began to stir up strife with her Colonies.... The Stamp Act of 1765 aroused the indignation of every thinking and self-respecting freeman. But nowhere did the flame of resentment burn more fiercely than in the province of New York.Brandow then describes the impact of the news of Lexington and Concord:

News traveled very slowly in those days, but all of it finally reached the inhabitants of this district and kindled the same fires in their breasts as it had elsewhere. But when they came to talk about armed resistance to England's encroachments, here, as in other localities, there was a diversity of opinion, and heated discussions were sure to be held wherever men congregated. But when the news came that British soldiers had wantonly spilt American blood, at Lexington and Concord, many of the wavering went over to the majority and decided to risk their all for liberty. Some, however, remained loyal to the king. In this they were no doubt conscientious, and their liberty of conscience was quite generally respected except in the cases of those violent partisans who talked too much, or who took up arms for Britain against their neighbors or gave succor or information to the enemy.

The news of the battle of Lexington reached New York on the 23d of April, just after Schuyler [a prominent citizen of Saratoga who had been serving as a delegate to the Provincial Congress in New York City] had started for his home. It followed him up the river, but did not overtake him till he reached Saratoga, on Saturday afternoon the 29th. The news was then six days old in New York and ten days old in Boston.A mere two weeks later, the inhabitants of Saratoga were electrified by the news that the British Fort Ticonderoga, just a few miles to the north had been seized by the Green Mountain Boys from Vermont under the command of Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold. The following December, many local farmers were impressed into service to help transport several cannon that had been captured at the fort. Brandow’s account continues:

The next day after the receipt of the aforesaid news Schuyler, as was his custom, attended divine service at the old (Dutch) Reformed Church, then standing in the angle of the river and Victory roads. John P. Becker, who was present at the same service, writes of it thus : "The first intelligence which gave alarm to our neighborhood, and indicated the breaking asunder of the ties which bound the colonies to the mother country, reached us on Sunday morning. We attended at divine service that day at Schuyler's Flats. I well remember, notwithstanding my youth, the impressive manner with which, in my hearing, my father told my uncle that blood had been shed at Lexington. The startling intelligence spread like fire among the congregation. The preacher was listened to with very little attention. After the morning discourse was finished, and the people were dismissed, we gathered about Gen. Philip Schuyler for further information.... On this occasion he confirmed the intelligence already received, and expressed his belief that an important crisis had arrived which must sever us forever from the parent country."

Among those in this vicinity who assisted in that work was Peter Becker... who lived across the river from Schuylerville. Col. Henry Knox, who afterward became the noted General, and chief of artillery, was sent on to superintend their removal. He first caused to be constructed some fifty big wooden sleds. The cannon selected for removal were nine to twenty-four pounders, also several howitzers. They already had been transported from Ticonderoga to the head of Lake George. From four to eight horses were hitched to each sled, so that when once under way, they made an imposing cavalcade. They were brought down this way to Albany, taken across the river, thence down through Kinderhook to Claverack, thence east to Springfield, Mass. There the New Yorkers were dismissed to their homes, and New England ox teams took their places.These artillery pieces were famously used by Washington on Dorcester Heights to help drive the British ships from Boston Harbor. According to Knox's diary, the sleds used to transport them were requested by Knox in a letter to Squire Palmer of Stillwater on 11 December 1775, at which point several men from the area, including Becker were sent north to Lake George to help. The cannon made their way south and arrived in Saratoga on 24 December where Knox and his men stopped for dinner. They woke Christmas morning to two feet of fresh snow and continued south to Albany.

Was Samuel among those who participated in the transportation of the cannons? If not, he and his family would at least have been witnesses to the commotion. We know they were living at their Stillwater homestead as early as 1769. I imagine it would have been at once exciting and terrifying for 9-year-old Daniel to watch these events unfold. Whatever the case may be, Samuel's revolutionary credentials must have been fairly well established by the time of his election to the committee in November 1776.

Monday, March 8, 2010

McBrides at Saratoga During American Revolution

Spurred by some excellent sleuthing by Gerald Lowell Christiansen, published on the Belnap Family site, I have been sniffing around for an old map of the Battle of Saratoga. Christiansen located a reference to a 97.15-acre farm owned by Samuel McBride in the late 18th century near Stillwater, Saratoga County, New York, in a farm survey book in the Albany Count Courthouse. The book calls it the "McBride farm so called," presumably because it had recently changed hands and now belonged a Mrs. Mary Livingston, but was still referred to as the "McBride farm." The Saratoga County Deed Book U, 336, gives all the gory details about the size, shape, and location of the lot. I refer you to Christiansen's research notes for more on this.

This farm would have been located smack in the middle of the series of conflicts known collectively as the Battle of Saratoga. This battle, a fateful and history-laden moment of the American Revolution, culminated with the surrender of 9,000 British troops under the command of Gen. Burgoyne late in 1777, and was a critical victory for the colonists. It has been credited with materially aiding Benjamin Franklin in his negotiations with France to obtain financial and military aid for the war.

One of the skirmishes of this battle took place on October 7, 1777. Known as the Second Battle of Bemis Heights, it witnessed the heroic (albeit insubordinate) charge of Benedict Arnold through British and Hessian lines, compromising the enemy rearguard and forcing their retreat. At the climax of his reckless assault, Arnold was shot in the leg near a British redoubt, a wound not so deep as the wound his reputation would later sustain when he was turned by the British.

A little sniffing around revealed this map, originally created by 19th-century historian Benson J. Lossing and published in his 1850 book, A Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution. A diligent researcher, Lossing toured the width and breadth of the United States interviewing the children of war veterans, surveying battlegrounds, and collecting documentary evidence, all in an attempt to portray the battles of the Revolution as accurately as possible. The result is a priceless treasury that features not only his written history but dozens of illustrations including this map depicting the Battle of Bemis Heights:

The exciting part for me was to see the name "S. MC.BRIDE" at the top left corner of the map (click to enlarge some - I am working on getting a much higher res scan of this map). This appears to be Samuel McBride's Stillwater farm, a clearing nestled between two hills, just north of the Wilber Basin Road and east of the Quaker's Springs Road. Interestingly, it is situated immediately west of Breyman's Redoubt where Benedict Arnold received his wound. Here is the current location on Google Maps:

The exciting part for me was to see the name "S. MC.BRIDE" at the top left corner of the map (click to enlarge some - I am working on getting a much higher res scan of this map). This appears to be Samuel McBride's Stillwater farm, a clearing nestled between two hills, just north of the Wilber Basin Road and east of the Quaker's Springs Road. Interestingly, it is situated immediately west of Breyman's Redoubt where Benedict Arnold received his wound. Here is the current location on Google Maps:State Rd. 32 is the Quaker's Springs Road. If you click on the terrain view on Google Maps you can easily make out the finger-shaped hill to the west of the farm (assuming the cabin on the Lossing Map represents the location of the farm) as well as the hills to the east. There is a stone monument to Arnold's charge on the former location of Breyman's Redoubt on those hills. From what I understand, the traitor's name is omitted. Anybody want to plan a trip to the area?

According to Christiansen's notes, Samuel McBride was listed as a member of the Saratoga Regiment as early as 1780, three years after this battle. Some questions:

What was Samuel and Margaret's experience during this battle? Their farm was situated squarely in the middle of the British camp, behind enemy lines. How were they treated? Did they participate in any way? Did they engage in sabotage or mind their own business? Was their farm damaged in any way? Did they help treat the wounded after the battle? Did the family evacuate the property before, during or after the battle?

Their son Daniel, my fifth-great-grandfather was Samuel's son. He was born (according to his son Reuben) in Stillwater in 1766, making him an eleven-year-old boy at the time of the battle and a mere 14-yeard-old when his father joined the Saratoga Regiment. These are important facts in Daniel's life.

Research Tip: Don't Neglect the Unit Journal

I love finding research tips and notes on other blogs and sites. I thought I would share a couple of ideas from my own experience that might be useful to someone. Especially if that someone is doing research on a family member who participated in World War II.

The National Archives II in College Park, Maryland is a fantastic place to study America's military history. It houses a massive collection of original documents ranging from Field Orders to After Action Reports to Combat interviews. It also has an enormous photograph collection of Signal Corps and other photography.

Chances are, if your grandfather or other family member participated in World War II, you'll find a wealth of information about his or her experience at Archives II. However, let me temper your expectations a bit: Do not go there expecting to find stories about your ancestor neatly written up for you. The material in Archives II is in a very raw state. It requires the hand of a patient researcher to coax out its treasures. The staff is very friendly and knowledgeable and can help you get started. From that point, you have to get a little creative.

The following presupposes that you know the unit, preferably the company (for example, Company F, 414th Infantry Regiment) to which your family member belonged. This information can be found on their service records, discharge papers, citations, pay stubs; just about any official document they may have saved.

There is a box or series of boxes containing the combat paper trail for each U.S. Army Division (my experience is with the papers of the 104th Infantry Division and the 3rd Armored Division). The boxes contain an eclectic mix of first hand documents. Some (regimental histories, after action reports) contain prose accounts of the dispositions, movements, and actions of the unit, and it is tempting to just order copies of those and call it a day.

My advice: Don't stop there. Infantry and armored regiments kept a Unit Journal. The main content of the Unit Journal is a minute-by-minute log of all of the company and battalion reports during combat. These terse, sometimes monotonous reports say things like "1230 F Co strafed friendly fire 100 yds S of 89" or "1845 1st Bl reporting A Co astride rd at 124." Obviously, the first part of the message is the time the report was received at regimental HQ. The subsequent information describes the disposition of a given unit at that specific time.

The beauty of these tweet-sized bits of information is that they are contemporary to the extreme. These reports were forwarded and logged in real time, making them incredibly valuable and usually very accurate primary source material.

Don't be daunted or discouraged by the sheer size of the Journal or the volume of messages it contains. Once you get the hang of reading them, you can very easily scan them to find the reports that pertain to the company to which your family member belonged.

Now for the fun part. The numbers designating the unit's location refer to numbered objectives that that were plotted on map overlays prepared during combat for the use of the unit commanders. The objectives were usually natural (ridges, hills, ponds) or man-made (bridges, crossroads, landmarks, towns) features of the landscape. These overlays (on vellum or tissue paper) and their corresponding maps are often included in the same boxes of materials as the Unit Journals themselves.

Using the maps/overlays and the Unit Journal, you can begin to plot very precisely the location of your family member at any given moment during during his or her tour of duty. Here are some possible uses for this kind of information:

1. Create an outline onto which you can graft your more anecdotal source material

2. Create and share a Google Map with the dates and locations of events

3. Clarify the sequence of events for certain battles

4. Organize a battlefield tour featuring blow-by-blow historical commentary

I have even been able to identify the location of certain stories in my grandpa's memoir based solely on the unit journal data and maps when the timing or physical features described were sufficiently unique.

Now, before you put the Unit Journal back in the box, peruse the appendices. You will usually find a list of combat casualties: the names and dates of battle deaths, injuries, and so forth. This can be helpful in several ways. Obviously, from the statistical perspective you get a very quick idea which were the hardest fought engagements.

I have also used these lists to pinpoint the dates and location of certain undated events in my grandfather's memoir, since he occasionally named individuals who died or were injured in his stories. Just locate their name in the combat casualties list and you have a date. Find the date on your Unit Journal plot and you have a location.

The National Archives II in College Park, Maryland is a fantastic place to study America's military history. It houses a massive collection of original documents ranging from Field Orders to After Action Reports to Combat interviews. It also has an enormous photograph collection of Signal Corps and other photography.

Chances are, if your grandfather or other family member participated in World War II, you'll find a wealth of information about his or her experience at Archives II. However, let me temper your expectations a bit: Do not go there expecting to find stories about your ancestor neatly written up for you. The material in Archives II is in a very raw state. It requires the hand of a patient researcher to coax out its treasures. The staff is very friendly and knowledgeable and can help you get started. From that point, you have to get a little creative.

The following presupposes that you know the unit, preferably the company (for example, Company F, 414th Infantry Regiment) to which your family member belonged. This information can be found on their service records, discharge papers, citations, pay stubs; just about any official document they may have saved.

There is a box or series of boxes containing the combat paper trail for each U.S. Army Division (my experience is with the papers of the 104th Infantry Division and the 3rd Armored Division). The boxes contain an eclectic mix of first hand documents. Some (regimental histories, after action reports) contain prose accounts of the dispositions, movements, and actions of the unit, and it is tempting to just order copies of those and call it a day.

My advice: Don't stop there. Infantry and armored regiments kept a Unit Journal. The main content of the Unit Journal is a minute-by-minute log of all of the company and battalion reports during combat. These terse, sometimes monotonous reports say things like "1230 F Co strafed friendly fire 100 yds S of 89" or "1845 1st Bl reporting A Co astride rd at 124." Obviously, the first part of the message is the time the report was received at regimental HQ. The subsequent information describes the disposition of a given unit at that specific time.

The beauty of these tweet-sized bits of information is that they are contemporary to the extreme. These reports were forwarded and logged in real time, making them incredibly valuable and usually very accurate primary source material.

Don't be daunted or discouraged by the sheer size of the Journal or the volume of messages it contains. Once you get the hang of reading them, you can very easily scan them to find the reports that pertain to the company to which your family member belonged.

Now for the fun part. The numbers designating the unit's location refer to numbered objectives that that were plotted on map overlays prepared during combat for the use of the unit commanders. The objectives were usually natural (ridges, hills, ponds) or man-made (bridges, crossroads, landmarks, towns) features of the landscape. These overlays (on vellum or tissue paper) and their corresponding maps are often included in the same boxes of materials as the Unit Journals themselves.

Using the maps/overlays and the Unit Journal, you can begin to plot very precisely the location of your family member at any given moment during during his or her tour of duty. Here are some possible uses for this kind of information:

1. Create an outline onto which you can graft your more anecdotal source material

2. Create and share a Google Map with the dates and locations of events

3. Clarify the sequence of events for certain battles

4. Organize a battlefield tour featuring blow-by-blow historical commentary

I have even been able to identify the location of certain stories in my grandpa's memoir based solely on the unit journal data and maps when the timing or physical features described were sufficiently unique.

Now, before you put the Unit Journal back in the box, peruse the appendices. You will usually find a list of combat casualties: the names and dates of battle deaths, injuries, and so forth. This can be helpful in several ways. Obviously, from the statistical perspective you get a very quick idea which were the hardest fought engagements.

I have also used these lists to pinpoint the dates and location of certain undated events in my grandfather's memoir, since he occasionally named individuals who died or were injured in his stories. Just locate their name in the combat casualties list and you have a date. Find the date on your Unit Journal plot and you have a location.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)